The Evolution of the U.S. Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy

In 2005, three high-resolution commercial remote sensing satellite companies served as the flagships of what appeared to be a growing remote sensing industry in the United States. Commercial satellite imagery was raising the profile of remote sensing solutions to prospective government and private-sector users. Investors were bullish, and with companies like Google showing interest, and the U.S. Government signing long-term contracts, the future of the commercial satellite imagery looked promising.

Five years later, the quantity and quality of, and demand for, commercial imagery have all increased tremendously. This article looks at the early years of commercial satellite imaging, provides an update on the current state and, on the eve of new EnhancedView contract awards from the U.S. Government, speculates on its future.

Establishing a Presence

Before Colorado-based Space Imaging established the commercial market by successfully launching IKONOS, the world’s first high-resolution earth-imaging satellite, in 1999, analysts projected rapid market adoption and significant short- and long-term growth. DigitalGlobe launched QuickBird in October 2001. The companies grew internationally, driven by eager customers who had purchased their own ground stations. However, the industry had difficulty proving its untested business models to non-DoD civil agencies, state and local governments and the private sector. While the defense and intelligence community had a long heritage of using overhead imagery, the integration of a new technology into commercial markets was taking longer than anticipated.

By early 2002, the national security establishment was becoming more dependent upon high-resolution commercial imagery as a result of burgeoning post-9/11 intelligence and mapping requirements. The Pentagon increasingly relied on IKONOS and QuickBird to shoulder the non-classified, routine imagery requirements of the U.S. Government satellites so those aging, overworked systems could focus on sensitive, time-critical imagery collections.

In May 2002, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice directed the Space Policy Coordinating Committee of the National Security Council (NSC) to undertake a review of “U.S. policy on commercial remote sensing and on foreign access to remote sensing space capabilities.” Rice’s directive initiated the process that would change the U.S. Government relationship with the slow-growing commercial satellite industry and dramatically improve its prospects.

Director of Central Intelligence George Tenet followed Rice’s directive with a one-page unclassified  memorandum to Lt. Gen. (ret.) James Clapper, NIMA’s director, underscoring this policy shift. In the June 2002 memo, NIMA was directed to “take the lead for the intelligence community in communicating this policy to the U.S. commercial imagery industry to ensure them of our commitment.” The objective of the new initiative, according to Tenet, was to “stimulate as quickly as possible” and “maintain for the foreseeable future” a “robust commercial space imagery industry.”

Rice’s directive and Tenet’s memorandum to NIMA were heartening news for the industry. To grow, formal contracts ensuring a steady stream of revenue in exchange for a steady stream of imagery were needed.

NIMA awarded the first high-resolution imagery purchase contracts, called ClearView, to the commercial data providers in 2002. A year later, NIMA announced it would become an early investor in the commercial industry’s next-generation satellites.

On April 25, 2003, President Bush authorized the “U.S. Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy” (National Security Presidential Directive-27), superseding the 1994 Presidential Decision Directive-23 (PDD-23), U.S. Policy on Foreign Access to Remote Sensing Space Capabilities, signed by President Clinton. The fundamental goal of this policy is to advance and protect U.S. national security and foreign policy interests by maintaining the nation’s leadership in remote sensing space activities and by sustaining and enhancing the U.S. remote sensing industry.

The new policy defined commercial imagery as a vital component of U.S. national security and a critical factor in the nation’s global scientific and technical competitiveness. NIMA’s early procurement efforts under the ClearView contracts evolved into the NextView program, a billion dollar procurement program with a five-year life span.

The White House policy formally recognized what all the commercial satellite imagery industry’s players already knew – that the health of the industry is a critical component of U.S. national security – and underscored the U.S. Government’s intention to support the industry’s viability. The policy helped solidify and broaden the need for geospatial technology in the national security arena, and it has fueled significant growth for the geospatial community within the U.S. Government’s civil agencies.

The White House Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy ensured that U.S. Government support would continue and increase, allowing the industry to expand its relations with the non-DoD civil and commercial sectors.

Gaining Acceptance

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (the NGA, formerly NIMA) awarded the first NextView contract to DigitalGlobe in October 2003 and the second NextView contract to Space Imaging (now GeoEye, Inc.) in September 2004. The awards were worth about $500 million each. The NextView program was designed to ensure that the NGA had access to commercial imagery to provide timely, relevant and accurate geospatial intelligence to support its mission. The contracts guaranteed the availability of high-resolution imagery from both satellites and provided the NGA with greater access, priority tasking rights, volume area coverage and broad licensing terms for sharing imagery with all potential mission partners.

As a result of the NextView contracts, DigitalGlobe launched WorldView-1 in September 2007 and GeoEye launched GeoEye-1 in September 2008. These NextView satellites provide the NGA with millions of square kilometers of imagery every month.

In January 2008, the NGA completed a re-negotiation of the NextView DigitalGlobe imagery acquisition contract from a pay-per-order structure to a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with a single monthly $12.5-million fee, more flexible rights and increased imagery volumes. In May 2008, the NGA opened discussions with GeoEye for a similar agreement, which was signed in December 2008. The NGA began receiving millions of square kilometers of imagery per month from each company in return for a guaranteed payment of $12.5 million per month as long as each company met a series of stringent metrics.

With both companies operating NextView satellites and with SLAs in place, the NGA is now looking at a next-generation commercial electro-optical imagery service and a follow-on program to NextView. In April 2009, the Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense announced their intent to modernize the nation’s aging satellite-imagery architecture by upgrading the sophisticated government-owned satellite systems and enhancing the use of U.S. commercial providers under the successor program to NextView, EnhancedView.

A Seat at the Table

EnhancedView is one part of a larger satellite imagery strategy announced April 7, 2009 by U.S. Director of National Intelligence Admiral Dennis Blair to serve both the military and intelligence community. Commonly referred to as the Two-plus-Two plan, the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office would purchase and operate two exquisite-class spy satellites as part of the new electro-optical satellite imaging plan approved by President Obama.

The unique capabilities of these satellites, evolved from existing designs, would give the nation a timely, and often decisive, information advantage. The second part of this plan stated the Department of Defense and the intelligence community would increase the use of imagery available through U.S. commercial providers. This additional capability would provide our government with more flexibility to respond to unforeseen challenges.

“Imagery is a core component of our national security that supports our troops, foreign policy, homeland security and the needs of our intelligence community,” Blair said. “Our proposal is an integrated, sustainable approach based on cost, feasibility and timeliness that meets the needs of our country now and puts in place a system to ensure that we will not have imagery gaps in the future.

“When it comes to supporting our military forces and the safety of Americans, we cannot afford any gaps in collection,” Blair added. “We are living with the consequences of past mistakes in acquisition strategy, and we cannot afford to do so again. We’ve studied this issue, know the right course and need to move forward now.”

The NGA anticipates making multiple awards under EnhancedView and will make use of an SLA concept that would include advanced payments for delivery of imagery. EnhancedView award announcements are expected in the spring 2010.

Presently, GeoEye and DigitalGlobe are the only two commercial satellite imagery companies in the market for the U.S. Government’s latest request for proposal, EnhancedView; however, the bidding process is open to all aerospace and defense companies and is expected to be competitive.

Conclusion: An Eye to the Future

In anticipation of an EnhancedView award, GeoEye is already building its next satellite, GeoEye-2, which could have a ground resolution as fine as a quarter meter. GeoEye has maintained it would not commit to building and launching its next satellite, GeoEye-2, on an accelerated schedule without a government contract or guarantee in place. If the company wins an EnhancedView award, it could launch GeoEye-2 in late 2012.

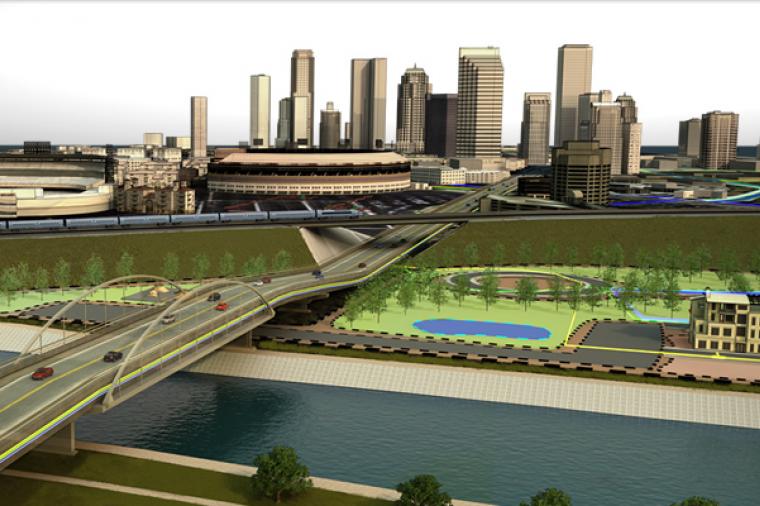

In the past, images like the one captured by GeoEye-1 of the nuclear enrichment facility under construction near Qum, Iran that appeared on the front page of the New York Times on September 29, 2009, used to be highly classified. Today, such images are available to the general public from commercial satellites.

In this exciting age of transparency, the partnerships formed between the U.S. Government and the commercial satellite industry through the ClearView, NextView and, soon, EnhancedView programs serve as great examples of how public-private partnerships should work.

Commercial satellite imaging clearly has earned its seat at the table, and it will remain at the table for years to come.

Lori Ward, Director, Commercial Sales GeoEye

Originially published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 11

Liz Kalweit, GeoEye corporate writer/editor, contributed to this article.

Lori Ward’s Bio:

Lori Ward joined GeoEye in October of 2008 and is responsible for North American commercial business development and direct sales. Lori has over 11 years of industry experience, primarily in the commercial aerospace sector in both Canada and the United States.

Prior to joining GeoEye, Lori was the Director of Sales for North and South America at DigitalGlobe, GeoEye’s closest competitor in the high resolution commercial aerospace industry. She works with customers in both Canada and the United States and has managed projects in both public and private sectors worldwide. Lori has over 14 years of Geographic Information Systems, Remote Sensing and Mapping experience and holds a Bachelor of Science in Geography from the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.

memorandum to Lt. Gen. (ret.) James Clapper, NIMA’s director, underscoring this policy shift. In the June 2002 memo, NIMA was directed to “take the lead for the intelligence community in communicating this policy to the U.S. commercial imagery industry to ensure them of our commitment.” The objective of the new initiative, according to Tenet, was to “stimulate as quickly as possible” and “maintain for the foreseeable future” a “robust commercial space imagery industry.”

Rice’s directive and Tenet’s memorandum to NIMA were heartening news for the industry. To grow, formal contracts ensuring a steady stream of revenue in exchange for a steady stream of imagery were needed.

NIMA awarded the first high-resolution imagery purchase contracts, called ClearView, to the commercial data providers in 2002. A year later, NIMA announced it would become an early investor in the commercial industry’s next-generation satellites.

On April 25, 2003, President Bush authorized the “U.S. Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy” (National Security Presidential Directive-27), superseding the 1994 Presidential Decision Directive-23 (PDD-23), U.S. Policy on Foreign Access to Remote Sensing Space Capabilities, signed by President Clinton. The fundamental goal of this policy is to advance and protect U.S. national security and foreign policy interests by maintaining the nation’s leadership in remote sensing space activities and by sustaining and enhancing the U.S. remote sensing industry.

The new policy defined commercial imagery as a vital component of U.S. national security and a critical factor in the nation’s global scientific and technical competitiveness. NIMA’s early procurement efforts under the ClearView contracts evolved into the NextView program, a billion dollar procurement program with a five-year life span.

The White House policy formally recognized what all the commercial satellite imagery industry’s players already knew – that the health of the industry is a critical component of U.S. national security – and underscored the U.S. Government’s intention to support the industry’s viability. The policy helped solidify and broaden the need for geospatial technology in the national security arena, and it has fueled significant growth for the geospatial community within the U.S. Government’s civil agencies.

The White House Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy ensured that U.S. Government support would continue and increase, allowing the industry to expand its relations with the non-DoD civil and commercial sectors.

Gaining Acceptance

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (the NGA, formerly NIMA) awarded the first NextView contract to DigitalGlobe in October 2003 and the second NextView contract to Space Imaging (now GeoEye, Inc.) in September 2004. The awards were worth about $500 million each. The NextView program was designed to ensure that the NGA had access to commercial imagery to provide timely, relevant and accurate geospatial intelligence to support its mission. The contracts guaranteed the availability of high-resolution imagery from both satellites and provided the NGA with greater access, priority tasking rights, volume area coverage and broad licensing terms for sharing imagery with all potential mission partners.

As a result of the NextView contracts, DigitalGlobe launched WorldView-1 in September 2007 and GeoEye launched GeoEye-1 in September 2008. These NextView satellites provide the NGA with millions of square kilometers of imagery every month.

In January 2008, the NGA completed a re-negotiation of the NextView DigitalGlobe imagery acquisition contract from a pay-per-order structure to a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with a single monthly $12.5-million fee, more flexible rights and increased imagery volumes. In May 2008, the NGA opened discussions with GeoEye for a similar agreement, which was signed in December 2008. The NGA began receiving millions of square kilometers of imagery per month from each company in return for a guaranteed payment of $12.5 million per month as long as each company met a series of stringent metrics.

With both companies operating NextView satellites and with SLAs in place, the NGA is now looking at a next-generation commercial electro-optical imagery service and a follow-on program to NextView. In April 2009, the Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense announced their intent to modernize the nation’s aging satellite-imagery architecture by upgrading the sophisticated government-owned satellite systems and enhancing the use of U.S. commercial providers under the successor program to NextView, EnhancedView.

A Seat at the Table

EnhancedView is one part of a larger satellite imagery strategy announced April 7, 2009 by U.S. Director of National Intelligence Admiral Dennis Blair to serve both the military and intelligence community. Commonly referred to as the Two-plus-Two plan, the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office would purchase and operate two exquisite-class spy satellites as part of the new electro-optical satellite imaging plan approved by President Obama.

The unique capabilities of these satellites, evolved from existing designs, would give the nation a timely, and often decisive, information advantage. The second part of this plan stated the Department of Defense and the intelligence community would increase the use of imagery available through U.S. commercial providers. This additional capability would provide our government with more flexibility to respond to unforeseen challenges.

“Imagery is a core component of our national security that supports our troops, foreign policy, homeland security and the needs of our intelligence community,” Blair said. “Our proposal is an integrated, sustainable approach based on cost, feasibility and timeliness that meets the needs of our country now and puts in place a system to ensure that we will not have imagery gaps in the future.

“When it comes to supporting our military forces and the safety of Americans, we cannot afford any gaps in collection,” Blair added. “We are living with the consequences of past mistakes in acquisition strategy, and we cannot afford to do so again. We’ve studied this issue, know the right course and need to move forward now.”

The NGA anticipates making multiple awards under EnhancedView and will make use of an SLA concept that would include advanced payments for delivery of imagery. EnhancedView award announcements are expected in the spring 2010.

Presently, GeoEye and DigitalGlobe are the only two commercial satellite imagery companies in the market for the U.S. Government’s latest request for proposal, EnhancedView; however, the bidding process is open to all aerospace and defense companies and is expected to be competitive.

Conclusion: An Eye to the Future

In anticipation of an EnhancedView award, GeoEye is already building its next satellite, GeoEye-2, which could have a ground resolution as fine as a quarter meter. GeoEye has maintained it would not commit to building and launching its next satellite, GeoEye-2, on an accelerated schedule without a government contract or guarantee in place. If the company wins an EnhancedView award, it could launch GeoEye-2 in late 2012.

In the past, images like the one captured by GeoEye-1 of the nuclear enrichment facility under construction near Qum, Iran that appeared on the front page of the New York Times on September 29, 2009, used to be highly classified. Today, such images are available to the general public from commercial satellites.

In this exciting age of transparency, the partnerships formed between the U.S. Government and the commercial satellite industry through the ClearView, NextView and, soon, EnhancedView programs serve as great examples of how public-private partnerships should work.

Commercial satellite imaging clearly has earned its seat at the table, and it will remain at the table for years to come.

Lori Ward, Director, Commercial Sales GeoEye

Originially published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 11

Liz Kalweit, GeoEye corporate writer/editor, contributed to this article.

Lori Ward’s Bio:

Lori Ward joined GeoEye in October of 2008 and is responsible for North American commercial business development and direct sales. Lori has over 11 years of industry experience, primarily in the commercial aerospace sector in both Canada and the United States.

Prior to joining GeoEye, Lori was the Director of Sales for North and South America at DigitalGlobe, GeoEye’s closest competitor in the high resolution commercial aerospace industry. She works with customers in both Canada and the United States and has managed projects in both public and private sectors worldwide. Lori has over 14 years of Geographic Information Systems, Remote Sensing and Mapping experience and holds a Bachelor of Science in Geography from the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.

memorandum to Lt. Gen. (ret.) James Clapper, NIMA’s director, underscoring this policy shift. In the June 2002 memo, NIMA was directed to “take the lead for the intelligence community in communicating this policy to the U.S. commercial imagery industry to ensure them of our commitment.” The objective of the new initiative, according to Tenet, was to “stimulate as quickly as possible” and “maintain for the foreseeable future” a “robust commercial space imagery industry.”

Rice’s directive and Tenet’s memorandum to NIMA were heartening news for the industry. To grow, formal contracts ensuring a steady stream of revenue in exchange for a steady stream of imagery were needed.

NIMA awarded the first high-resolution imagery purchase contracts, called ClearView, to the commercial data providers in 2002. A year later, NIMA announced it would become an early investor in the commercial industry’s next-generation satellites.

On April 25, 2003, President Bush authorized the “U.S. Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy” (National Security Presidential Directive-27), superseding the 1994 Presidential Decision Directive-23 (PDD-23), U.S. Policy on Foreign Access to Remote Sensing Space Capabilities, signed by President Clinton. The fundamental goal of this policy is to advance and protect U.S. national security and foreign policy interests by maintaining the nation’s leadership in remote sensing space activities and by sustaining and enhancing the U.S. remote sensing industry.

The new policy defined commercial imagery as a vital component of U.S. national security and a critical factor in the nation’s global scientific and technical competitiveness. NIMA’s early procurement efforts under the ClearView contracts evolved into the NextView program, a billion dollar procurement program with a five-year life span.

The White House policy formally recognized what all the commercial satellite imagery industry’s players already knew – that the health of the industry is a critical component of U.S. national security – and underscored the U.S. Government’s intention to support the industry’s viability. The policy helped solidify and broaden the need for geospatial technology in the national security arena, and it has fueled significant growth for the geospatial community within the U.S. Government’s civil agencies.

The White House Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy ensured that U.S. Government support would continue and increase, allowing the industry to expand its relations with the non-DoD civil and commercial sectors.

Gaining Acceptance

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (the NGA, formerly NIMA) awarded the first NextView contract to DigitalGlobe in October 2003 and the second NextView contract to Space Imaging (now GeoEye, Inc.) in September 2004. The awards were worth about $500 million each. The NextView program was designed to ensure that the NGA had access to commercial imagery to provide timely, relevant and accurate geospatial intelligence to support its mission. The contracts guaranteed the availability of high-resolution imagery from both satellites and provided the NGA with greater access, priority tasking rights, volume area coverage and broad licensing terms for sharing imagery with all potential mission partners.

As a result of the NextView contracts, DigitalGlobe launched WorldView-1 in September 2007 and GeoEye launched GeoEye-1 in September 2008. These NextView satellites provide the NGA with millions of square kilometers of imagery every month.

In January 2008, the NGA completed a re-negotiation of the NextView DigitalGlobe imagery acquisition contract from a pay-per-order structure to a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with a single monthly $12.5-million fee, more flexible rights and increased imagery volumes. In May 2008, the NGA opened discussions with GeoEye for a similar agreement, which was signed in December 2008. The NGA began receiving millions of square kilometers of imagery per month from each company in return for a guaranteed payment of $12.5 million per month as long as each company met a series of stringent metrics.

With both companies operating NextView satellites and with SLAs in place, the NGA is now looking at a next-generation commercial electro-optical imagery service and a follow-on program to NextView. In April 2009, the Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense announced their intent to modernize the nation’s aging satellite-imagery architecture by upgrading the sophisticated government-owned satellite systems and enhancing the use of U.S. commercial providers under the successor program to NextView, EnhancedView.

A Seat at the Table

EnhancedView is one part of a larger satellite imagery strategy announced April 7, 2009 by U.S. Director of National Intelligence Admiral Dennis Blair to serve both the military and intelligence community. Commonly referred to as the Two-plus-Two plan, the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office would purchase and operate two exquisite-class spy satellites as part of the new electro-optical satellite imaging plan approved by President Obama.

The unique capabilities of these satellites, evolved from existing designs, would give the nation a timely, and often decisive, information advantage. The second part of this plan stated the Department of Defense and the intelligence community would increase the use of imagery available through U.S. commercial providers. This additional capability would provide our government with more flexibility to respond to unforeseen challenges.

“Imagery is a core component of our national security that supports our troops, foreign policy, homeland security and the needs of our intelligence community,” Blair said. “Our proposal is an integrated, sustainable approach based on cost, feasibility and timeliness that meets the needs of our country now and puts in place a system to ensure that we will not have imagery gaps in the future.

“When it comes to supporting our military forces and the safety of Americans, we cannot afford any gaps in collection,” Blair added. “We are living with the consequences of past mistakes in acquisition strategy, and we cannot afford to do so again. We’ve studied this issue, know the right course and need to move forward now.”

The NGA anticipates making multiple awards under EnhancedView and will make use of an SLA concept that would include advanced payments for delivery of imagery. EnhancedView award announcements are expected in the spring 2010.

Presently, GeoEye and DigitalGlobe are the only two commercial satellite imagery companies in the market for the U.S. Government’s latest request for proposal, EnhancedView; however, the bidding process is open to all aerospace and defense companies and is expected to be competitive.

Conclusion: An Eye to the Future

In anticipation of an EnhancedView award, GeoEye is already building its next satellite, GeoEye-2, which could have a ground resolution as fine as a quarter meter. GeoEye has maintained it would not commit to building and launching its next satellite, GeoEye-2, on an accelerated schedule without a government contract or guarantee in place. If the company wins an EnhancedView award, it could launch GeoEye-2 in late 2012.

In the past, images like the one captured by GeoEye-1 of the nuclear enrichment facility under construction near Qum, Iran that appeared on the front page of the New York Times on September 29, 2009, used to be highly classified. Today, such images are available to the general public from commercial satellites.

In this exciting age of transparency, the partnerships formed between the U.S. Government and the commercial satellite industry through the ClearView, NextView and, soon, EnhancedView programs serve as great examples of how public-private partnerships should work.

Commercial satellite imaging clearly has earned its seat at the table, and it will remain at the table for years to come.

Lori Ward, Director, Commercial Sales GeoEye

Originially published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 11

Liz Kalweit, GeoEye corporate writer/editor, contributed to this article.

Lori Ward’s Bio:

Lori Ward joined GeoEye in October of 2008 and is responsible for North American commercial business development and direct sales. Lori has over 11 years of industry experience, primarily in the commercial aerospace sector in both Canada and the United States.

Prior to joining GeoEye, Lori was the Director of Sales for North and South America at DigitalGlobe, GeoEye’s closest competitor in the high resolution commercial aerospace industry. She works with customers in both Canada and the United States and has managed projects in both public and private sectors worldwide. Lori has over 14 years of Geographic Information Systems, Remote Sensing and Mapping experience and holds a Bachelor of Science in Geography from the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.

memorandum to Lt. Gen. (ret.) James Clapper, NIMA’s director, underscoring this policy shift. In the June 2002 memo, NIMA was directed to “take the lead for the intelligence community in communicating this policy to the U.S. commercial imagery industry to ensure them of our commitment.” The objective of the new initiative, according to Tenet, was to “stimulate as quickly as possible” and “maintain for the foreseeable future” a “robust commercial space imagery industry.”

Rice’s directive and Tenet’s memorandum to NIMA were heartening news for the industry. To grow, formal contracts ensuring a steady stream of revenue in exchange for a steady stream of imagery were needed.

NIMA awarded the first high-resolution imagery purchase contracts, called ClearView, to the commercial data providers in 2002. A year later, NIMA announced it would become an early investor in the commercial industry’s next-generation satellites.

On April 25, 2003, President Bush authorized the “U.S. Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy” (National Security Presidential Directive-27), superseding the 1994 Presidential Decision Directive-23 (PDD-23), U.S. Policy on Foreign Access to Remote Sensing Space Capabilities, signed by President Clinton. The fundamental goal of this policy is to advance and protect U.S. national security and foreign policy interests by maintaining the nation’s leadership in remote sensing space activities and by sustaining and enhancing the U.S. remote sensing industry.

The new policy defined commercial imagery as a vital component of U.S. national security and a critical factor in the nation’s global scientific and technical competitiveness. NIMA’s early procurement efforts under the ClearView contracts evolved into the NextView program, a billion dollar procurement program with a five-year life span.

The White House policy formally recognized what all the commercial satellite imagery industry’s players already knew – that the health of the industry is a critical component of U.S. national security – and underscored the U.S. Government’s intention to support the industry’s viability. The policy helped solidify and broaden the need for geospatial technology in the national security arena, and it has fueled significant growth for the geospatial community within the U.S. Government’s civil agencies.

The White House Commercial Remote Sensing Space Policy ensured that U.S. Government support would continue and increase, allowing the industry to expand its relations with the non-DoD civil and commercial sectors.

Gaining Acceptance

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (the NGA, formerly NIMA) awarded the first NextView contract to DigitalGlobe in October 2003 and the second NextView contract to Space Imaging (now GeoEye, Inc.) in September 2004. The awards were worth about $500 million each. The NextView program was designed to ensure that the NGA had access to commercial imagery to provide timely, relevant and accurate geospatial intelligence to support its mission. The contracts guaranteed the availability of high-resolution imagery from both satellites and provided the NGA with greater access, priority tasking rights, volume area coverage and broad licensing terms for sharing imagery with all potential mission partners.

As a result of the NextView contracts, DigitalGlobe launched WorldView-1 in September 2007 and GeoEye launched GeoEye-1 in September 2008. These NextView satellites provide the NGA with millions of square kilometers of imagery every month.

In January 2008, the NGA completed a re-negotiation of the NextView DigitalGlobe imagery acquisition contract from a pay-per-order structure to a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with a single monthly $12.5-million fee, more flexible rights and increased imagery volumes. In May 2008, the NGA opened discussions with GeoEye for a similar agreement, which was signed in December 2008. The NGA began receiving millions of square kilometers of imagery per month from each company in return for a guaranteed payment of $12.5 million per month as long as each company met a series of stringent metrics.

With both companies operating NextView satellites and with SLAs in place, the NGA is now looking at a next-generation commercial electro-optical imagery service and a follow-on program to NextView. In April 2009, the Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense announced their intent to modernize the nation’s aging satellite-imagery architecture by upgrading the sophisticated government-owned satellite systems and enhancing the use of U.S. commercial providers under the successor program to NextView, EnhancedView.

A Seat at the Table

EnhancedView is one part of a larger satellite imagery strategy announced April 7, 2009 by U.S. Director of National Intelligence Admiral Dennis Blair to serve both the military and intelligence community. Commonly referred to as the Two-plus-Two plan, the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office would purchase and operate two exquisite-class spy satellites as part of the new electro-optical satellite imaging plan approved by President Obama.

The unique capabilities of these satellites, evolved from existing designs, would give the nation a timely, and often decisive, information advantage. The second part of this plan stated the Department of Defense and the intelligence community would increase the use of imagery available through U.S. commercial providers. This additional capability would provide our government with more flexibility to respond to unforeseen challenges.

“Imagery is a core component of our national security that supports our troops, foreign policy, homeland security and the needs of our intelligence community,” Blair said. “Our proposal is an integrated, sustainable approach based on cost, feasibility and timeliness that meets the needs of our country now and puts in place a system to ensure that we will not have imagery gaps in the future.

“When it comes to supporting our military forces and the safety of Americans, we cannot afford any gaps in collection,” Blair added. “We are living with the consequences of past mistakes in acquisition strategy, and we cannot afford to do so again. We’ve studied this issue, know the right course and need to move forward now.”

The NGA anticipates making multiple awards under EnhancedView and will make use of an SLA concept that would include advanced payments for delivery of imagery. EnhancedView award announcements are expected in the spring 2010.

Presently, GeoEye and DigitalGlobe are the only two commercial satellite imagery companies in the market for the U.S. Government’s latest request for proposal, EnhancedView; however, the bidding process is open to all aerospace and defense companies and is expected to be competitive.

Conclusion: An Eye to the Future

In anticipation of an EnhancedView award, GeoEye is already building its next satellite, GeoEye-2, which could have a ground resolution as fine as a quarter meter. GeoEye has maintained it would not commit to building and launching its next satellite, GeoEye-2, on an accelerated schedule without a government contract or guarantee in place. If the company wins an EnhancedView award, it could launch GeoEye-2 in late 2012.

In the past, images like the one captured by GeoEye-1 of the nuclear enrichment facility under construction near Qum, Iran that appeared on the front page of the New York Times on September 29, 2009, used to be highly classified. Today, such images are available to the general public from commercial satellites.

In this exciting age of transparency, the partnerships formed between the U.S. Government and the commercial satellite industry through the ClearView, NextView and, soon, EnhancedView programs serve as great examples of how public-private partnerships should work.

Commercial satellite imaging clearly has earned its seat at the table, and it will remain at the table for years to come.

Lori Ward, Director, Commercial Sales GeoEye

Originially published in [acronym] magazine, Issue 11

Liz Kalweit, GeoEye corporate writer/editor, contributed to this article.

Lori Ward’s Bio:

Lori Ward joined GeoEye in October of 2008 and is responsible for North American commercial business development and direct sales. Lori has over 11 years of industry experience, primarily in the commercial aerospace sector in both Canada and the United States.

Prior to joining GeoEye, Lori was the Director of Sales for North and South America at DigitalGlobe, GeoEye’s closest competitor in the high resolution commercial aerospace industry. She works with customers in both Canada and the United States and has managed projects in both public and private sectors worldwide. Lori has over 14 years of Geographic Information Systems, Remote Sensing and Mapping experience and holds a Bachelor of Science in Geography from the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.