Jetlag is a mind killer.

Anyone who has ever had to regularly brave the US Airport Circus to make sure the checks don’t bounce at the end of the month, understands that jetlag isn’t something that only hits you the day after you travel. The confused, fuzzy-headed filter will occasionally slam down on your poor hapless brain anywhere from 24 to 168 hours after landing back in your home time zone.

Delayed jetlag hit me like a sack of bricks yesterday as I tried to explain to a client how to attach an Elastic Network Interface (ENI) to a network isolated instance to support remote administration. I didn’t have the luxury of recall, since I wasn’t driving the console myself and I was fighting with my eye lids for control of my consciousness. To top it off, we were also working on a wireless connection that seemed to be playing merry hell with our AWS Console session.

Needless to say, hilarity ensued as Murphy (aka Murphy’s Law) played with us like marionettes. At the end of the session we did get the connection up, and I was reminded that AWS, in an attempt to keep things simple, obscures what is really going on when dealing with network interfaces, Elastic IP’s, and routing tables. I knew this, but in my fog I assumed that everyone understood the subtleties that are hidden in plain site when working with the console.

Another Way to Look at AWS Networking

As such, and in an attempt to transform my foggy struggles at the end of a simple consulting session into a teachable moment, I’d like to give you another way to look at AWS networking that isn’t new, but is often obscured by the inherent assumptions in many AWS diagrams.

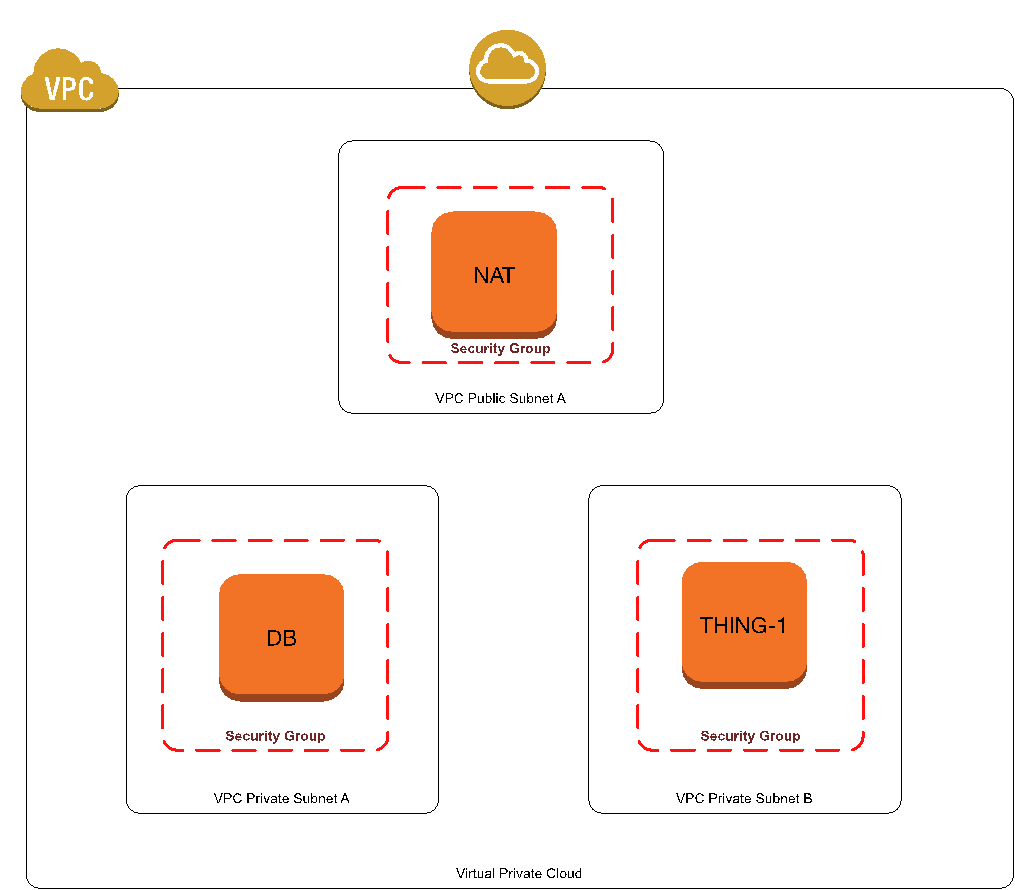

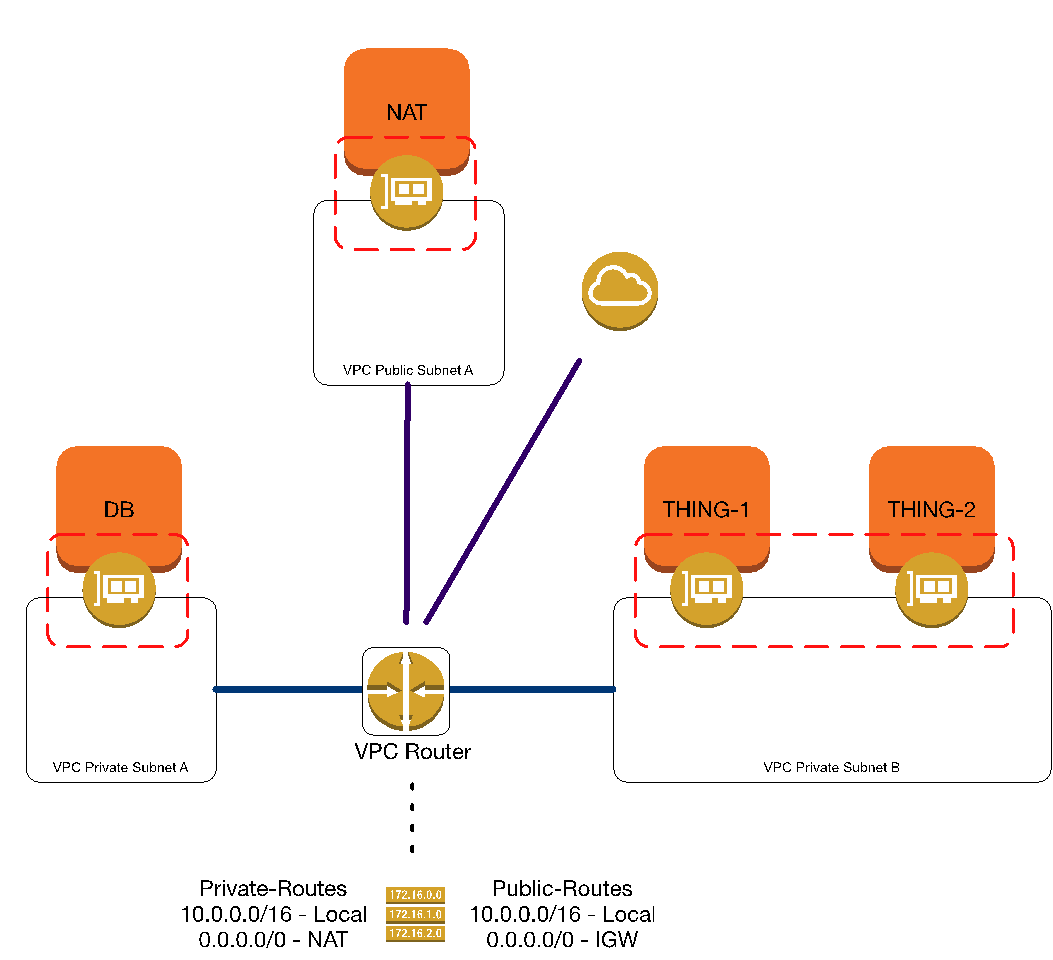

This is typically how AWS diagrams show the relationships of instances, subnets, the VPC, and Security Groups. I often drill down deeper, but many examples and descriptions show that the instance has a direct membership INSIDE of a subnet, and that the Internet Gateway (IGW) is lurking near the public subnets waiting, with baited breath, to route traffic. In reality, it’s not that way at all.

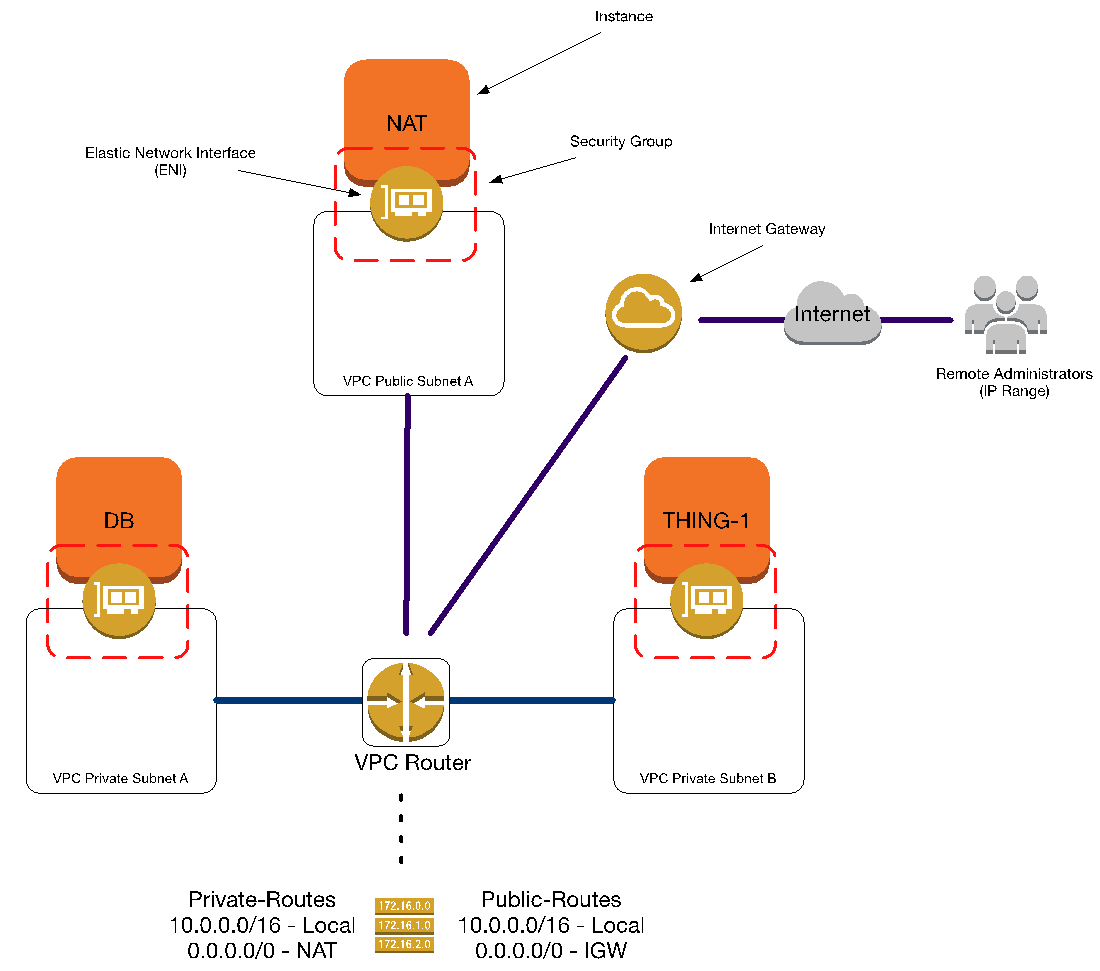

The way we really virtually wire all the instances together in a VPC is much more like the diagram above. It’s not as pretty and symmetrical, but conceptually you should always be thinking about your VPC networking like this. When you do, the security and functionality spring forward.

ENIs are attached to instances and assigned to subnets. An instance’s connection, or anchor, to subnets is through the ENIs. Otherwise, they float on the edge of subnets. Or if you prefer, hook into a subnet trunk, though the ENI.

The VPC router links all the subnets within a VPC together, referencing route tables that subnets are associated with. The router makes the call on how traffic travels between the subnets, and to ingress/egress points like the IGW or Virtual Gateways (VGWs). Finally, the Security Groups encapsulate the ENIs – not the instances – so that the Security Groups, ENIs, and subnets act as membranes to protect and service the instances.

In this context, it is also easier to show/visualize the true nature of Security Group memberships. Since traditional firewalling typically defended a subnet, sometimes the mind will drift back to that assumption. Looking at the VPC from an ENI-centric view changes that for the better.

So drilling into the use case I was trying to explain to my client earlier, we have a need to preform maintenance or house keeping functions on our DB server. However, it is in a private subnet. We can take advantage of the magic of ENIs and Elastic IPs (EIPs) to get the job done securely when we don’t have the luxury of using a Virtual Private Network (VPN) connection to come in over a permanent established backchannel.

The first part of this adventure is to build an ENI to handle the traffic. We need to do this because right now, the DB server is only connected to the Private Subnet A, and Private Subnet A uses the NAT to communicate out of the VPC to the Internet. That is only a one-way path leading out of the VPC that can’t support incoming SSH sessions into the DB instance, or interactive tools like Navicat.

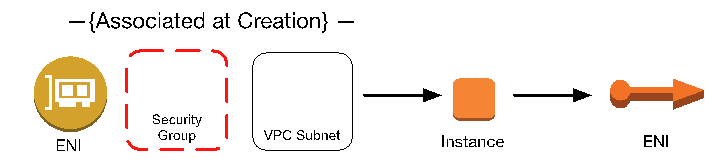

When we build the ENI, we specify the subnet that the ENI is attached to, and what Security Group it is attached to as well.

Identifying the Connectivity Issue

In the AWS Architecture and SysOps classes I teach, I stress that there are two places to look first when you are having a connectivity issue: Security Groups and routing tables. 90% of the time there is a snafu with one of those two configuration points. When attaching your ENI to a Security Group to support this use case, make sure you have configured the group to support the bare necessity of ports, and make absolutely sure you have specified a source address or source IP range to allow the traffic. While SSH can weather exposure fairly well if you are using key authentication, a system with RDP open to the world will quickly find itself a new occupation as a Bit Torrent node.

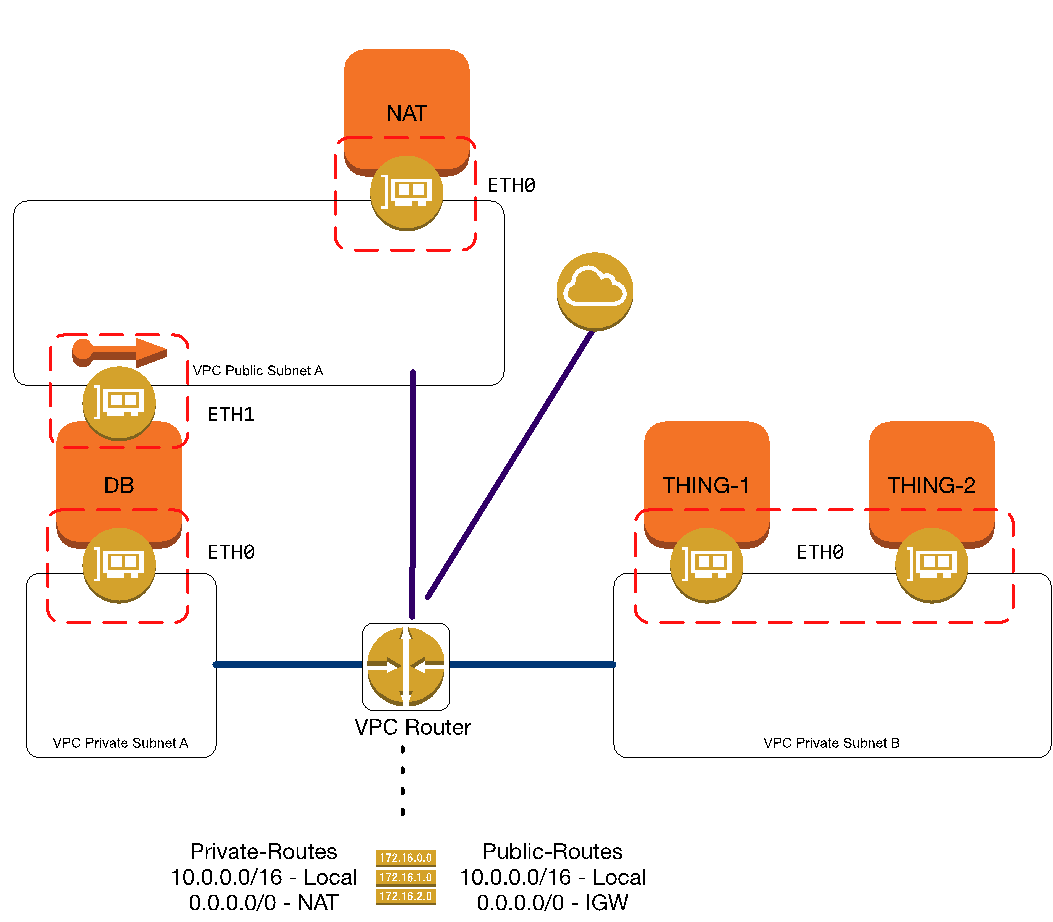

Specifically, we will need to create a Security Group for our use case, let’s call it “MySQL-Direct-Access”, and open up ports tcp/22 and tcp/3306 from an exact IP address used by our SQL team. We will assign the ENI to that group, and to the Public A Subnet.

After that, we will attach the ENI to the DB server, and associate an EIP with the ENI. That changes our logical landscape to look like this

The routing table attached to the Public Subnet will route traffic to and from our new ENI attached to our DB server. It will show up as ETH1 on the instance and in the AWS Console / API. The Security Group will allow ports tcp/22 and tcp/3306 to be accessed by a specific system or IP grouping of systems. When there is no need for the interface to be active, we can detach it from the DB instance. We could also give the DB or SA teams specific permissions in the AWS platform that would let them attach it when needed, or use a script to bring it online.

This is a pretty simple use case for a condition that comes up more often than you’d think. I’d like to stress that the best way to handle this is to have a Direct Connect (DX) or a Virtual Private Network (VPN) into the VPC to support privileged and/or trusted connections. That said, every situation and customer is a unique snowflake, and this “Management ENI” technique is infinitely better than just tossing your DB servers into a public subnet.

Now, if you all don’t mind, I’m going to go find another cup of coffee to keep away Jetlag Gremlins.