How BIM Makes the IPD Model Possible – a Q&A with BuroHappold

Not all Ivy League schools have massive endowments and bank accounts. Some have to get more creative when looking to build new facilities on a budget – or simply embrace innovative new approaches to design and construction. And that’s exactly what Brown University did when they decided to build their new Engineering Research Center – a state of the art facility designed to help the university attract the most talented engineering faculty, researchers and students.

Spearheaded by BuroHappold Engineering, Shawmut Design and Construction and the KieranTimberlakearchitecture firm, Brown University’s Engineering Research Center was among the first institutional labs in the country constructed utilizing an innovative new approach to project design and construction called the integrated project delivery (IPD) model.

This model helped to ensure that the Engineering Research Center was delivered on time and on budget. But it also created unique communication, collaboration and logistical challenges for all of the stakeholders involved. Luckily, today’s advanced building information modeling (BIM) solutions provided the tools necessary to overcome these hurdles.

In fact, the project was so successful that it was the recipient of an AEC Excellence Award from Autodesk, which was presented at last year’s Autodesk University. These awards are presented only to those infrastructure design, building design, and construction projects that best utilize technology to evolve and redefine the design and construction process.

To learn more about the Brown University Engineering Research Center, the IPD model and why this project was selected for such a prestigious award, we recently sat down with Paul McGilly, an Associate Principal at BuroHappold Engineering and a BIM expert. Here is what Paul had to say:

GovDesignHub (GDH): Can you tell our readers a bit about the Brown University Engineering Research Center? What was this building intended for? When did the project start and finish?

Paul McGilly: The new Engineering Research Center at Brown University is an 81,330 square-foot facility featuring cutting edge research labs, clean rooms, an imaging suite, and flexible workspaces.

Brown elevated its engineering department to the status of School of Engineering in 2010, and needed a unified home on campus. The engineering program was fragmented into three buildings with only tangential connections in both program and design. Brown commissioned KieranTimberlake architects to design the new Engineering Research Center in 2014, with Buro Happold providing Structural and MEP Engineering as well as Façade Consultation and Lighting Design services.

The project was one of the first institutional labs in the nation to be delivered with the integrated project delivery (IPD) model, where the owner, architect and contractor are mutually responsible for development, stakeholder engagement, and keeping the project construction on target and on budget.

The project began in 2014 and was occupied in November 2017, 3 months ahead of schedule.

GDH: How is IPD different from traditional models and approaches to construction? Why did Brown University decide to utilize this model?

Paul McGilly: To truly understand the differences, we have to first look at the traditional construction methods.

First, there’s “Design-Bid-Build,” where an owner develops contract documents with an architect or an engineer consisting of a set of blueprints and detailed specifications. Bids are then solicited from contractors based on these documents and a contract is then awarded to the lowest responsive and responsible bidder.

Another, more traditional method is “Design-Build,” where an owner develops a conceptual plan for a project, then solicits bids from joint ventures of architects and/or engineers and builders for the design and construction of the project.

IPD is a project delivery method in which the interests of the primary teams are aligned in such a way that the members can be integrated for optimal project performance. This results in a collaborative, value-based process that delivers high-outcome results to the entire building team.

Brown University utilized this method since it has fewer students, has lower revenues and a smaller endowment than other Ivy League schools. So, they needed to make their money go further. By implementing the IPD method they developed a long-term relationship with their trade partners, which enabled consistency on how they build their facilities. It also enabled them to develop a set of standards and an efficient workflow.

GDH: In 2014, when this project kicked off, were many institutional labs and other similar buildings built using the IPD model?

Paul McGilly: As far as we are aware, the Engineering Research Center at Brown University is one of – if not the – first institutional lab to implement IPD in the country.

GDH: What unique challenges faced this project? Were any of them a result of the IPD model?

Paul McGilly: The key to fully benefitting from the IPD model is team collaboration and relationship building between the design and trade partners. These parties need to have an “in it together” mentality.

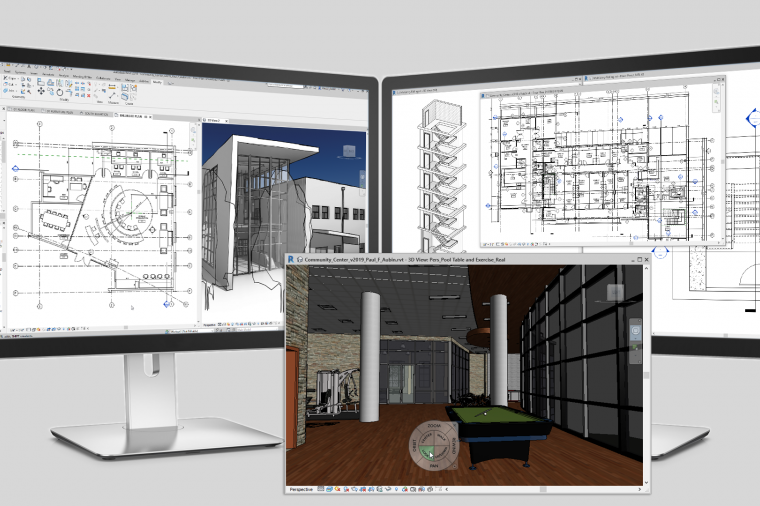

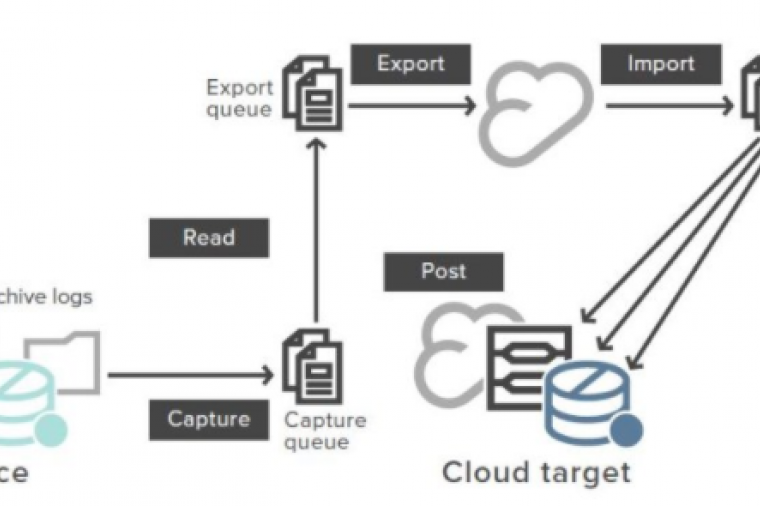

To facilitate this, from project kick off, team members worked in a common digital environment – Autodesk’s BIM 360 – to ensure the highest level of collaboration among team members, despite being in disparate physical locations.

Through the use of the BIM 360 modules the team was able to sync and share models effortlessly across disciplines and platforms, allowing immediate clash resolution. This real-time coordination occurred through the design process and the construction/ assembly phase, where fabrication drawings were produced directly from the models.

To stay within budget the team used model-based cost estimating. Costs were tracked and reported weekly from dynamic schedules and take-offs generated from the models. These regular cost reports empowered designers and trade partners to make design decisions based on project budget. In addition, BIM models were used for construction sequencing and identifying opportunities for improvement allowing for project completion ahead of schedule.

GDH: What benefits did BIM deliver to the project?

Paul McGilly: The stakeholders decided that being able to share data seamlessly was a game changer for the project team, not only in cost and efficiencies, but for their own wellbeing. Normally, as deadlines approach, designers can work 50-60 hours per week.

However, by utilizing a cloud-based BIM platform, the design team was able to leverage their teams around their global offices, meaning designers avoided the exhaustion and stress of extended overtime hours. Overall, cloud-based work-sharing helped improve design work quality and avoid errors. These factors were decisive in hosting the project on BIM 360.

Another key benefit from utilizing BIM was project coordination, clash detection and model walkthroughs, which was done in BIM 360 Glue and Navisworks. This helped designers see updates and allowed architects to comment, in real-time, on how routing decisions met organizational criteria, making clash reporting and resolution more interactive and effective.

GDH: What was the end result? Did the IPD model and the use of BIM solutions benefit Brown University in the end?

Paul McGilly: Absolutely. The Engineering Research Center was an ambitious plan to expand the research efforts of the school, inspire and enable great science and engineering, and attract the best, most talented faculty, researchers, and students.

This project was the university’s first IPD effort deployed at a whole-building scale, and it serves as an example of efficient project delivery because the design team worked closely with the construction manager, Brown University and consultants. Together, these parties engaged the full range of IPD strategies, including: physical team location, early trade partner engagement, in-depth pull plan sessions, and implementation of Lean Design principals.

Early in the process, all involved parties coordinated on the development of an organizational framework by which progress would be measured – which was key in its success. The collective accountability, financial and data transparency, and collaborative dynamic of the IPD model fostered an environment that fostered flexibility for adaptation and streamlined response times.

GDH: We often hear of organizations utilizing their BIM models after the construction is done. Is Brown University doing that? How can those BIM models benefit them post-construction?

Paul McGilly: Brown University’s Facilities Management Team inherited the project BIM models, and is using them for operational purposes and to manage future research lab fit-outs.

During the design stage of the project, the design and trade partners collaborated in developing a workflow for identifying asset data requirements and how to integrate them into the model. This included electrical, mechanical, plumbing and fire protection equipment, along with fixtures.

The University’s facilities team can now benefit from this data for maintenance planning, warranty and commissioning – along with potential integration with the building BMS system. The data is there and ready to use whenever the university decides to utilize it.

Article originally posted on GovDesignHub.